Maître Jacques

“Jacques” traditionally means “learned”

The stories surrounding Maître Jacques come from the ancient tradition of “compagnons passants” (the fraternity known as “Maitre Jacques’ Children” – itinerant builders who had also “passed” into a state of heightened awareness), and from today’s “Compagnons passants des devoirs”. Their accounts say that Maître Jacques was born in the Pyrenees town of Carte. He was commanded by Hiram of Tyre, on behalf of King Solomon, to oversee the construction, in about 900 BC, of the Temple at Jerusalem. He was descended from those who covered the West with megaliths and dolmens. He was a “jars” (gander), a “Maître Jars”. As Master, he was initiated in the nature of stone: legend notes that he began work as a stone-cutter at the age of 15.

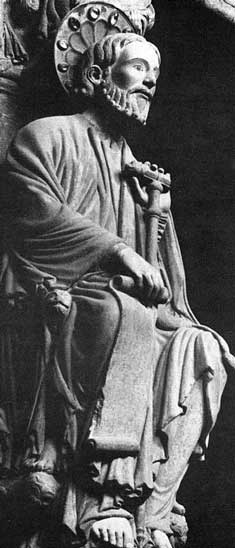

Saint Jacques le Majeur, a Jacques “of the baton”, carries the foreman’s measuring rod.

This same legend holds Maître Jacques responsable for the Jakin Pillar and perhaps even for the Pillar of Boaz.

The translators of the Bible generally render Jakin as meaning “he will make firm”, but in Basque this word means “savant” or “learned one”. As for Boaz, the usual translation is “in him is force”.

Some legends claim that he was “assassinated” by “the children of Père Soubise” (Benedictine order centered at Cluny). This was a way of illustrating that the Gothic impulse had effectively drowned the Romanesque. He is said to be buried at Sainte Baume (in the region of Marseille), in the same grotto as Mary Magdalen. Even today, titled Compagnons (indicated by the wearing of a ring in the left ear) go there to pay him homage.

Jacques is the generic name of the people of builders and peasants, people of stone and earth, pre-Celt, which moved throughout the Western and Mediterranean worlds. To them we owe the menhirs and dolmens, a great number of temples, the “gallo-Roman” style and the countless sacred buildings of the Christian era.

The “Path of Stars” (many, many of the places one stopped included “stella” in the name) was their university. In the eyries lost in the Sierra de Jaca, the old masters warmed their bones in the sun of the Pyrenees’ southern slopes. Their doors stood open and each was a shaman who, according to the corporation to which he belonged, taught his own speciality.